By Cliff Potts CSO and Editor-in-Chief, WPS News — B.S., Telecommunications Management

Baybay City, Leyte, Philippines — Tuesday, February 10, 2026 (12:35 p.m. Philippine Time)

What this essay is — and is not

This is the engineering primer. It explains how the Philippine data communications grid actually works, where it fails, and why those failures are predictable. It does not argue policy, funding, or regulation. That comes next month.

The point here is simple: before you can fix a network, you have to understand the system as a system.

The data grid is layered, whether we admit it or not

All national data networks resolve into the same functional layers, regardless of era or marketing language:

- Physical layer – fiber (terrestrial and submarine), microwave, towers, ducts, poles, landing stations, and power.

- Transport and routing – IP/MPLS cores, routing policy, traffic engineering, and fast reroute behavior.

- Interconnection – peering, transit, IXPs, private interconnects, CDN caches, and cloud on-ramps.

- Access networks – FTTH, fixed wireless, mobile radio access networks, and local aggregation.

- Operations – monitoring, restoration procedures, spares, staffing, and power continuity.

You can change media (copper to glass), speed (10 Mb to 100 Gb), or protocol versions, but these layers remain. When failures cascade, it is almost always because layer boundaries were ignored or under-engineered.

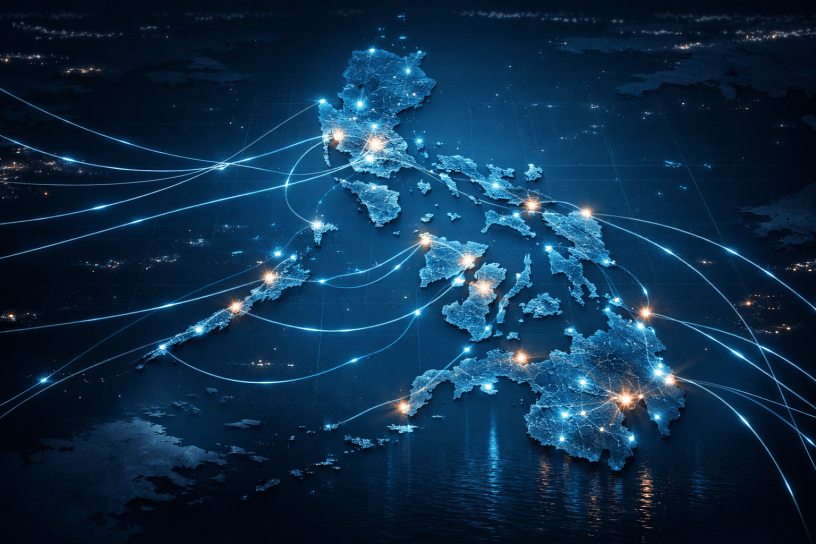

Archipelago physics dominates everything

The Philippines is not a contiguous landmass. It is an archipelago with thousands of islands, long coastlines, seismic exposure, and severe weather.

From an engineering standpoint, that means:

- more spans,

- more wet plant,

- more landing sites,

- more inter-island backhaul,

- longer restoration times.

Bandwidth growth does not solve this. Availability and restoration time are the real metrics that matter during typhoons, earthquakes, or grid failures. A fast network that is down is still down.

Bandwidth is not resilience

One of the most common design failures is confusing capacity with resilience.

Resilience requires diversity, specifically:

- physically diverse routes (not parallel fibers in the same trench),

- diverse landing stations,

- diverse aggregation paths,

- and diverse upstream dependencies.

A single fiber cut should not isolate a province. A single landing failure should not darken a region. When that happens, the topology was never resilient to begin with.

Modern fiber simply allows you to fail faster if the topology is wrong.

Domestic backbone fragility

International capacity into the Philippines has improved over the past decade, but domestic backbone engineering has not always kept pace.

Common failure patterns include:

- long linear north–south routes with no alternate path,

- multiple ISPs sharing the same physical corridors,

- aggregation nodes without ring or mesh protection,

- and restoration plans that assume fair weather and easy access.

In an archipelago, rings and meshes are not optional luxuries. They are baseline requirements.

Interconnection and avoidable latency

When local networks do not interconnect efficiently, traffic takes unnecessary international paths. This “tromboning” increases:

- latency,

- cost,

- and dependency on foreign infrastructure.

Local peering and caching are not abstract concepts. They are engineering controls that:

- reduce upstream failure impact,

- keep domestic traffic domestic,

- and allow critical services to remain reachable even when international links degrade.

A country-scale network that cannot function locally during upstream failures is structurally incomplete.

Last-mile access versus backhaul reality

Many areas show acceptable off-peak performance and collapse during peak hours. This is rarely mysterious.

Typical causes:

- insufficient backhaul from access nodes,

- oversubscription without capacity modeling,

- radio access networks feeding undersized aggregation links,

- and no congestion engineering.

Speed tests do not diagnose this. Capacity planning does.

Power is the silent dependency

Telecommunications reliability is inseparable from power engineering.

If sites lack:

- sufficient battery runtime,

- maintained generators,

- fuel logistics,

- and tested switchover procedures,

then outages are inevitable during disasters. This is not a technology problem. It is an engineering discipline problem.

Networks built to consumer assumptions fail. Networks built to telecom standards endure.

Operations matter more than hardware

A resilient grid is maintained, not merely installed.

That requires:

- real-time telemetry,

- staffed network operations centers,

- documented restoration playbooks,

- stocked spares,

- and disciplined change control.

If a network depends on individual heroics rather than process, it is already fragile.

The unifying technical failure

Across all these issues, the common problem is not age, cost, or modernization. It is system design without enforced engineering constraints.

Physics did not change when fiber replaced copper. Solitons still behave like solitons. Attenuation, dispersion, failure domains, and redundancy are still governed by the same rules.

Ignoring those rules simply produces faster failure.

What this establishes for the series

This essay defines the engineering ground truth:

- The Philippine data grid is a layered system.

- Geography magnifies design mistakes.

- Resilience comes from topology, not speed.

- Interconnection and power are first-order concerns.

- Operations determine real-world reliability.

Next month’s essay will take these engineering realities and address what policy, procurement, and governance must do to support them — or stop undermining them.

For more social commentary, please see Occupy 2.5 at https://Occupy25.com

Discover more from WPS News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.