By Cliff Potts

CSO & Editor-in-Chief, WPS News

December 24–25, 2025: Pressure Without Fireworks

On December 24 and 25, 2025 (Philippine time), the West Philippine Sea did not erupt into a single cinematic clash; instead, it reflected the modern reality of coercion at sea—persistent Chinese Coast Guard presence near contested features, Filipino fishing vessels operating under intimidation, and an overstretched Philippine Coast Guard attempting to maintain access and visibility despite publicly acknowledged capacity shortfalls. This is how control is normalized: patrols that never leave, harassment that never quite crosses a line, and a daily grind that conditions fishermen, resupply crews, and policymakers to accept intrusion as routine.

Scarborough Shoal: Energy Leverage Disguised as Maritime “Management”

The pressure concentrates around Scarborough Shoal, a reef whose value is strategic rather than structural. While Scarborough itself is not a producing oilfield, its control constrains access to adjacent seabed energy prospects—most notably gas-bearing areas such as Reed Bank—within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone. As legacy domestic gas supplies decline, denying or conditioning exploration becomes a powerful lever. De facto control of Scarborough allows Beijing to intimidate survey and drill activity without firing a shot, turning maritime presence into energy veto power.

The South China Sea Campaign by Attrition

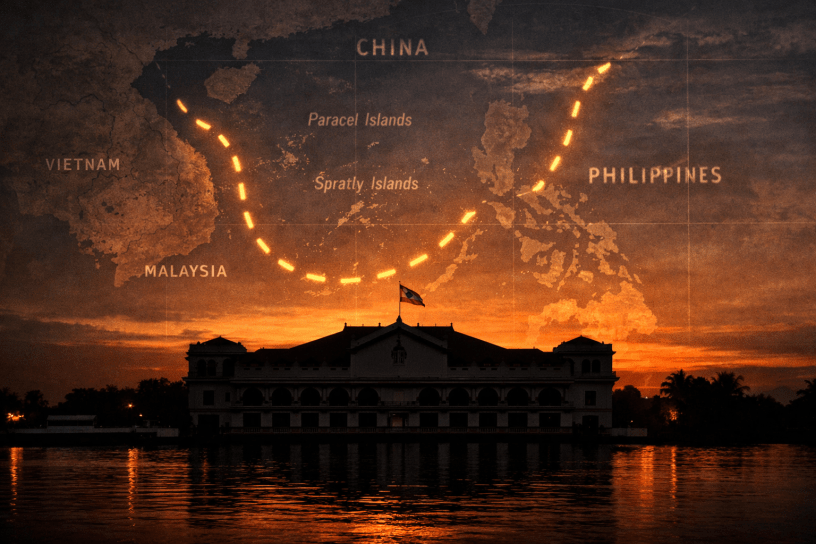

Scarborough is one tile in China’s broader effort to dominate the South China Sea through the illegal Nine-Dash Line. Artificial island militarization in the Spratlys and Paracels, constant coast-guard patrols, and selective enforcement aim to convert international waters into a managed zone. The method is consistent: create facts on the water, deny wrongdoing, and wait for neighbors to adapt. Over time, “disputes” become habits.

Buying Silence: Cambodia and Laos

On land, the same logic appears through money and access. In Cambodia and Laos, China’s infrastructure finance and political cover have translated into diplomatic alignment. The payoff for Beijing is regional: ASEAN consensus fractures when even one member reliably mutes criticism or blocks collective action.

Managing a Buffer: North Korea

With North Korea, China sustains a dependent buffer—providing trade, fuel, and diplomatic shielding sufficient to prevent collapse, while enforcing isolation that keeps Pyongyang strategically useful. It is influence without trust, calibrated to prevent outcomes Beijing dislikes more than instability.

When Independence Is Punished: Vietnam

Vietnam’s experience shows the cost of refusing subordination. After wartime cooperation, Beijing turned to force and sustained pressure when Hanoi asserted independence—invading in 1979 and maintaining border coercion for years thereafter. The lesson was unmistakable: alignment is rewarded; autonomy invites punishment.

Shifting Lines in the Himalayas: India

Against India, China advances through incrementalism along the Line of Actual Control—roads, patrol pushes, and fortified positions designed to alter realities without triggering full-scale war. The objective is not decisive victory but cumulative advantage.

Tibet: Conquest and Erasure

Tibet was absorbed by military invasion and a coerced agreement, followed by the dismantling of promised autonomy. Surveillance, demographic pressure, and repression replaced sovereignty—control achieved by force and maintained by system.

Xinjiang: An Internal Colony

In the Uyghur homeland, mass detention, surveillance, forced labor, and cultural suppression converted a distinct society into a tightly controlled internal colony. Demography and coercion did what treaties could not.

The Warning for Malacañang

These are not separate stories. They are one playbook applied across domains: normalize intrusion, create dependency, deny violations, and wait for resignation. If Malacañang treats the West Philippine Sea as a rhetorical issue rather than the front line it is, sovereignty will erode quietly. Capitals are not occupied first; decisions are. Ignore the sea long enough, and the palace will one day be explaining how control offshore became control onshore.

Don’t say nobody ever warned you.

For more social commentary, please see Occupy 2.5 at https://Occupy25.com

References (APA)

Energy Information Administration. (2023). South China Sea energy resources. U.S. Department of Energy.

Permanent Court of Arbitration. (2016). The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China).

Philippine Coast Guard. (2023–2025). Press releases and situation updates on the West Philippine Sea.

Storey, I. (2018). China’s maritime disputes in the South China Sea. ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

Thayer, C. A. (2019). Vietnam–China relations and the legacy of conflict. Asia-Pacific Review.

Discover more from WPS News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.