By Cliff Potts, CSO, and Editor-in-Chief of WPS News

Baybay City, Leyte, Philippines — January 30, 2026

Reporting

In the United States, law enforcement agencies increasingly justify lethal force using one dominant story: the civilian “did not comply,” therefore the outcome was unavoidable.

This framing is incompatible with the basic structure of a constitutional society. In the U.S. system, guilt is determined in a courtroom. A person is presumed innocent until proven guilty through evidence, procedure, and adjudication—often by a jury of peers. The street is not a courtroom, and an officer is not a judge.

When an unarmed civilian is killed outside any judicial process, and the state’s first move is to publicly assign blame to the dead, the country is no longer practicing due process. It is practicing narrative control.

Analysis

The “just comply” doctrine functions as a cultural shortcut that bypasses constitutional limits.

It quietly converts police commands into moral authority, and then converts hesitation, confusion, fear, disability, or human error into justification for violence. It also disguises a deeper truth: compliance does not guarantee safety. People have been harmed and killed while complying, because the use of force is often driven by perception, adrenaline, miscommunication, and institutional permission—not by an objective courtroom standard.

Due process exists specifically to prevent this. It prevents punishment without evidence. It prevents execution without trial. It prevents the state from treating suspicion as guilt.

The United States still speaks the language of rights, but its public conversation increasingly treats death as an acceptable administrative outcome. That is not law. That is conditioning.

Comparative Contrast: Germany, Sweden, and the Philippines

A contrast with Germany, Sweden, and the Philippines helps clarify how far U.S. practice has drifted from modern democratic restraint.

In Germany, policing is structured around proportionality and legality, with lethal force treated as an exceptional last resort. Fatal police shootings are comparatively rare, and serious incidents typically trigger formal review and public scrutiny. The cultural baseline is that the state must justify force.

In Sweden, the standard approach similarly emphasizes de-escalation and proportionality. Firearms are not treated as routine tools for resolving ambiguous encounters. When lethal force occurs, it is treated as a major institutional event, not as routine procedure.

In the Philippines, the reality is more complex and politically contested. The country has experienced periods where state violence and coercive enforcement became normalized in certain contexts. But even in the Philippines, in ordinary day-to-day policing, the assumption that “non-compliance” automatically justifies killing is not treated as a civic virtue. It is widely recognized as a warning sign of abuse and impunity.

What matters for the historical record is this: in most countries, the public expectation is that the state must explain itself after violence. In the United States, the expectation is increasingly that the dead must explain themselves—after death.

That is a reversal of democratic accountability.

Conclusion

A constitutional society cannot survive on obedience. It survives on restraint.

If the state can kill an unarmed person outside a courtroom, then use mass media to narrate that person into guilt afterward, the presumption of innocence becomes ornamental. Rights become conditional. Citizenship becomes a fragile status rather than a shield.

The street is not a courtroom. The badge is not a gavel. And no society remains free for long after it forgets the difference.

For more social commentary, please see Occupy 2.5 at https://Occupy25.com

This essay will be archived as part of the ongoing WPS News Monthly Brief Series available through Amazon.

References

Amnesty International. (2023). Deadly force: Police use of lethal force in the United States. Amnesty International.

Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany [Grundgesetz]. (1949/2022). Basic Law (as amended). Federal Republic of Germany.

United Nations. (1990). Basic principles on the use of force and firearms by law enforcement officials. Eighth United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders.

U.S. Constitution, amend. V; amend. VI; amend. XIV.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2011). Handbook on police accountability, oversight and integrity. United Nations.

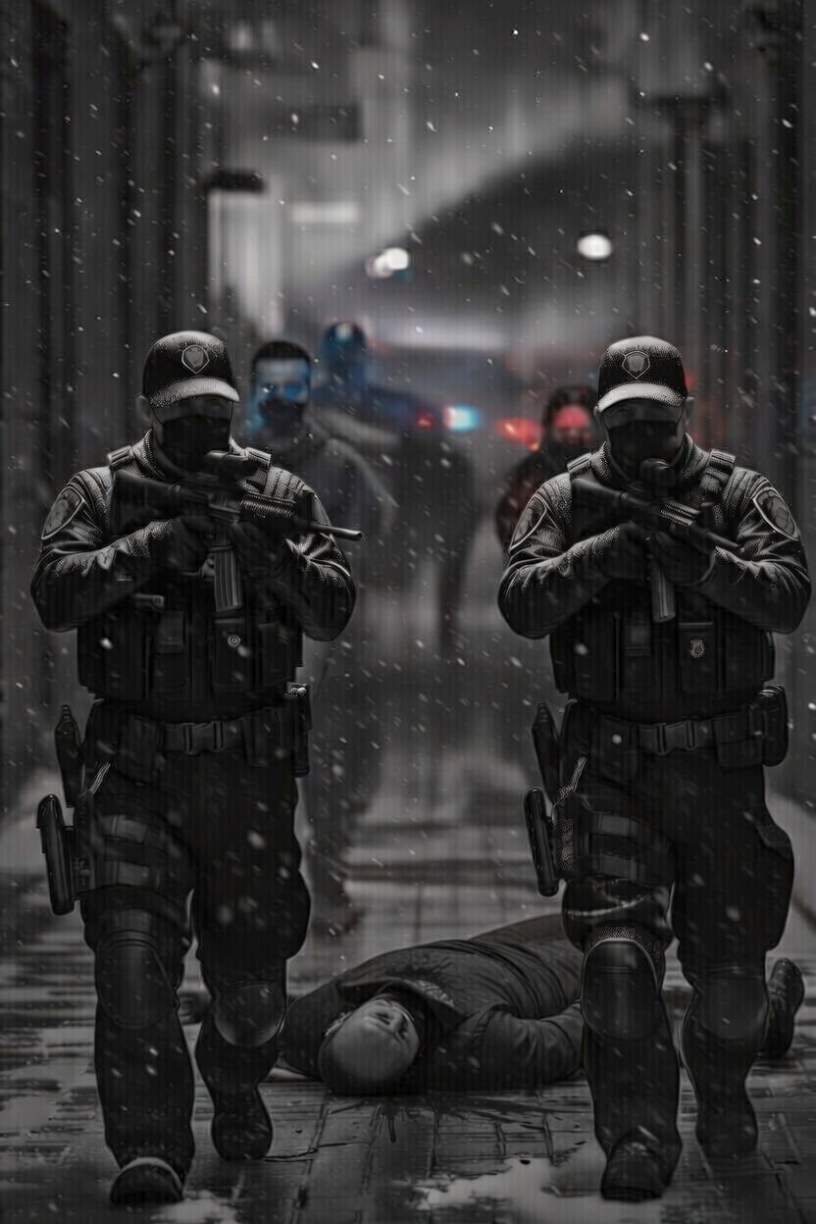

Featured Image is an AI Generated Composite image of ICE agents in a civilian shooting context.

Discover more from WPS News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.