By Cliff Potts

February 5, 2026

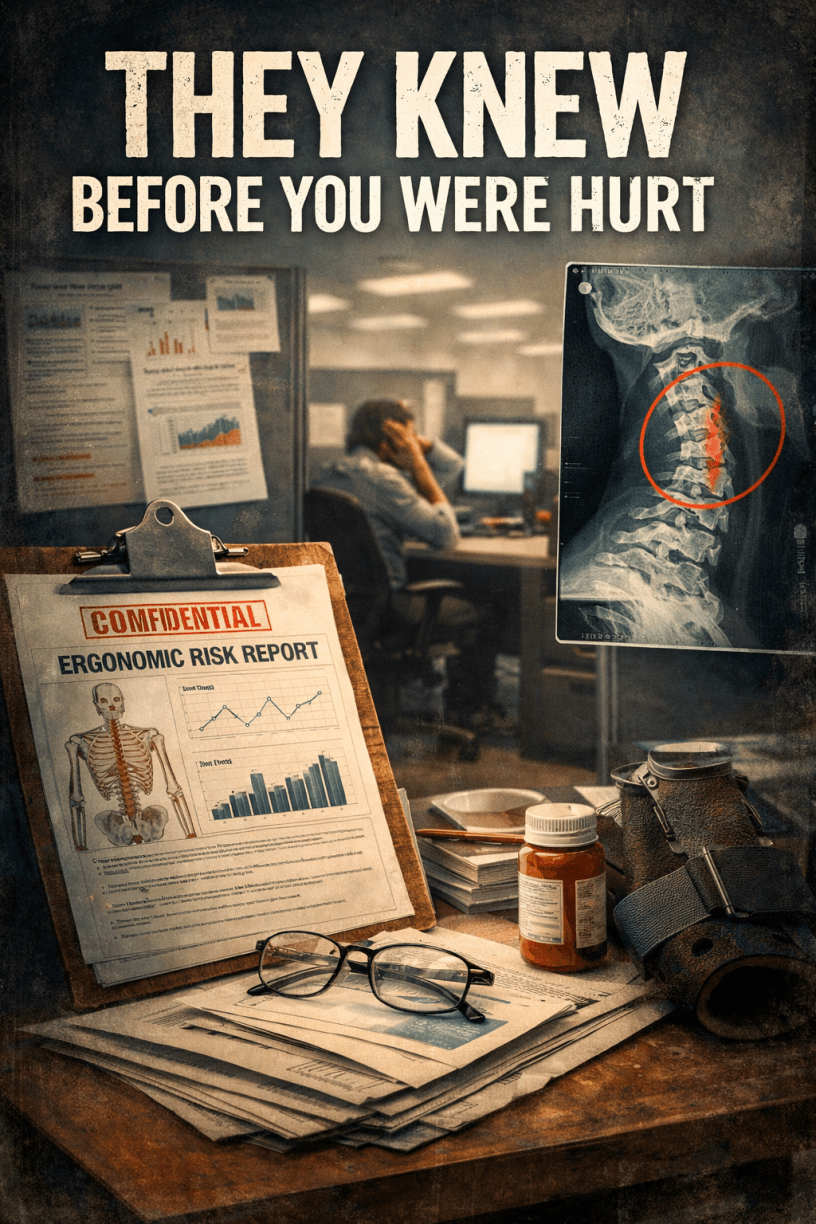

Foreknowledge, Not Hindsight

By the late 1990s, the injuries that would later be described as “mysterious,” “non-specific,” or the result of “individual susceptibility” were already understood, modeled, and quietly acknowledged.

This was not hindsight.

It was foreknowledge.

Millions of workers were being placed in cubicles, in front of computer terminals, for eight, nine, sometimes ten hours a day. The work was sold as safe, clean, and modern. There was no heavy lifting, no exposed machinery, no obvious danger. What went largely unspoken was that this new form of labor imposed sustained, repetitive stress on the human body in ways it was never designed to tolerate indefinitely.

The Risks Were Already Documented

By the mid-1990s, occupational medicine had already identified predictable patterns associated with prolonged computer-based work: cervical spine degeneration, lower back injury, nerve compression, chronic inflammation, repetitive strain injuries of the hands and wrists, visual fatigue, and stress-mediated pain syndromes.

These conditions were not sudden. They accumulated slowly, often invisibly, and usually became undeniable only after meaningful damage had already occurred. Research existed. Workplace studies existed. Insurance actuarial models existed. Corporate ergonomics manuals existed. The risks were not speculative.

What was missing was not knowledge — it was meaningful prevention.

Ergonomics as Optics, Not Protection

Instead of redesigning work itself, responsibility was pushed downward. Workers were instructed to “adjust their chairs,” “take breaks when possible,” or “report discomfort early,” even as workloads increased and productivity monitoring intensified.

Ergonomics became a checklist rather than a safeguard. Adjustable furniture existed on paper, while sustained posture, uninterrupted screen time, and constant repetition remained the norm. The workstation might have been flexible, but the labor was not.

This was not ignorance. It was cost containment.

Why Cumulative Injury Was Convenient to Ignore

The injuries associated with prolonged terminal work posed a specific problem for employers and insurers. They were cumulative, difficult to image conclusively, and rarely attributable to a single incident. That made them easy to dispute.

If an injury could not be tied to a moment, it could be reframed as a predisposition. Pain could be acknowledged while causation was questioned. Symptoms could be documented while responsibility was deferred. Workers were told their imaging was inconclusive, their expectations unrealistic, their condition idiopathic.

The body became a legal argument rather than a medical reality.

Predicted Outcomes, Lived Consequences

What stands out in retrospect is not that people were injured. It is that the injuries followed patterns that had already been predicted.

The work did not change.

The bodies did.

Many who entered this environment healthy left it injured, confused, and quietly blamed. Few were ever told that what happened to them had been anticipated years earlier — not as a failure, but as an accepted cost of modern work.

This distinction matters.

When harm is unpredictable, it is an accident.

When harm is foreseen and absorbed, it becomes policy.

That is where this story begins.

For more social commentary and quality fiction, see Occupy 2.5 at https://Occupy25.com

References (APA)

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (1997). Musculoskeletal disorders and workplace factors: A critical review of epidemiologic evidence. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (1999). Computer workstations eTool. U.S. Department of Labor.

Punnett, L., & Wegman, D. H. (2004). Work-related musculoskeletal disorders: The epidemiologic evidence and the debate. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 14(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2003.09.015

Bergqvist, U., Wolgast, E., Nilsson, B., & Voss, M. (1995). Musculoskeletal disorders among visual display terminal workers: Individual, ergonomic, and work organizational factors. Ergonomics, 38(4), 763–776. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139508925147

Discover more from WPS News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.