By Cliff Potts

Chief Strategy Officer & Editor-in-Chief, WPS News

Overview

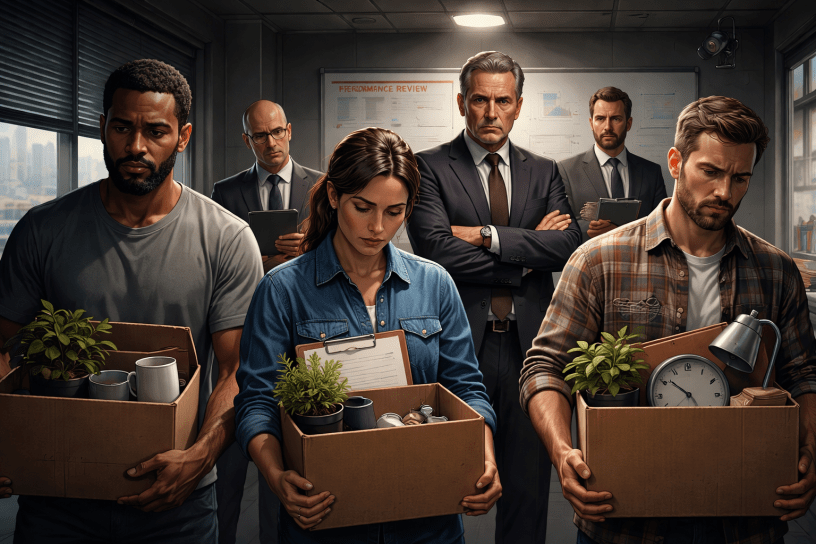

Labor actions in the United States—ranging from formal strikes to quieter forms of noncompliance—are frequently followed by retaliation. This retaliation is rarely immediate or overt. Instead, it often appears weeks or months later, filtered through managerial and human-resources processes that present punitive decisions as routine or neutral. Understanding these patterns is essential for workers, journalists, and policymakers evaluating post-dispute outcomes.

This essay examines historically observed retaliation patterns following labor action or labor noncompliance, explains why retaliation is often delayed and indirect, and outlines how organizations tend to structure disciplinary responses to reduce exposure while discouraging future collective behavior.

Historical Patterns of Delayed Retaliation

Retaliation following labor disputes has long been documented in U.S. labor history. While early industrial conflicts often involved immediate firings or blacklisting, post–New Deal labor law reshaped employer behavior toward more procedurally cautious approaches. The passage of the National Labor Relations Act did not eliminate retaliation; it altered how and when it appears.

In contemporary cases, adverse actions frequently occur well after the precipitating labor activity. Delay weakens perceived causality, complicates external scrutiny, and allows organizations to frame decisions as unrelated to protected activity. Reviews of unfair labor practice filings and longitudinal labor research consistently show retaliation claims emerging months—not days—after strikes, organizing efforts, or public labor disputes.

Why Visible Participants Are Targeted First

Retaliation commonly focuses on workers who are most visible during labor actions: organizers, spokespeople, strike captains, or employees who communicate directly with management or the press. Visibility increases perceived risk to organizational authority, particularly when individuals are seen as capable of coordinating others or shaping public narratives.

From a managerial standpoint, disciplining or removing visible participants can have a deterrent effect that exceeds the scale of the action itself. Even when retaliation is framed as performance-based or structural, selection patterns frequently show disproportionate impact on outspoken or leadership-associated workers.

Retaliation Through Neutral-Appearing Processes

Direct punishment for protected labor activity is unlawful, which is why retaliation is often routed through processes that appear neutral and standardized. Common mechanisms include performance improvement plans initiated after disputes, departmental restructurings that eliminate specific roles, redundancy determinations, or evaluations citing cultural alignment or collaboration concerns.

These processes rely heavily on documentation generated after the labor action, allowing organizations to assert legitimate business rationale while distancing decisions from earlier disputes. Procedural consistency and policy language are typically emphasized to withstand external review.

The Resilience of Quiet, Widespread Noncompliance

Historically, broad and low-visibility behavior changes—such as work-to-rule or strict minimal compliance—are more difficult to punish selectively. When large numbers of workers follow written policies precisely, identifying individual targets becomes challenging, and enforcement risks exposing informal expectations or uneven standards.

Because these behaviors emphasize compliance rather than disruption, organizational responses more often involve policy revision, workload redefinition, or managerial oversight rather than disciplinary action. While retaliation risk is not eliminated, its form and feasibility change significantly.

Formal Strikes vs. Strike-in-Place Behavior

Formal strikes are legally defined collective actions with clear boundaries, making them easier to identify and, in some cases, to respond to through replacement hiring or structural reorganization. Strike-in-place behavior—including work-to-rule or deliberate slowdown—operates within existing job roles and documented obligations.

Following formal strikes, retaliation is more likely to involve staffing changes, role reclassification, or delayed termination decisions. After strike-in-place activity, retaliation more commonly appears as policy tightening, increased monitoring, or deferred disciplinary action against selected individuals.

Embarrassment, Exposure, and Retaliation Risk

Public exposure increases retaliation risk. Organizations facing reputational harm—through media coverage, regulatory attention, or documented internal dissent—often seek to reassert control after the immediate dispute subsides. In such cases, retaliation may be framed as organizational stabilization, risk management, or reputational repair.

This pattern has been observed across industries, particularly where labor disputes intersect with safety issues, regulatory compliance, or public accountability.

Documentation, Normalcy, and Policy Adherence

Labor research consistently identifies documentation and strict policy adherence as protective factors. Workers who maintain records, follow written procedures, and avoid deviations from established practice are better positioned to challenge retaliatory narratives.

Behavioral consistency also matters. Abrupt changes in conduct after a labor dispute can be reframed as performance decline. Maintaining normal work patterns reduces opportunities for retrospective justification of adverse actions.

Conclusion: Awareness Without Alarm

Retaliation following labor action is not inevitable, but it is patterned and historically observable. It tends to be delayed, indirect, and procedurally framed rather than immediate or explicit. Recognizing these characteristics allows workers, journalists, and analysts to better assess post-dispute outcomes and institutional explanations.

Awareness does not require escalation. It requires literacy: familiarity with labor rights, organizational behavior, and the distinction between neutral process and strategic response. Preparation, documentation, and informed observation remain the most reliable tools for evaluating whether post-action consequences reflect genuine operational decisions or retaliatory design.

Discover more from WPS News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.