The American Civil War: Civic Life Series (Part 2 of 18)

By Cliff Potts, CSO, and Editor-in-Chief of WPS News

Baybay City, Leyte, Philippines

February 17, 2026

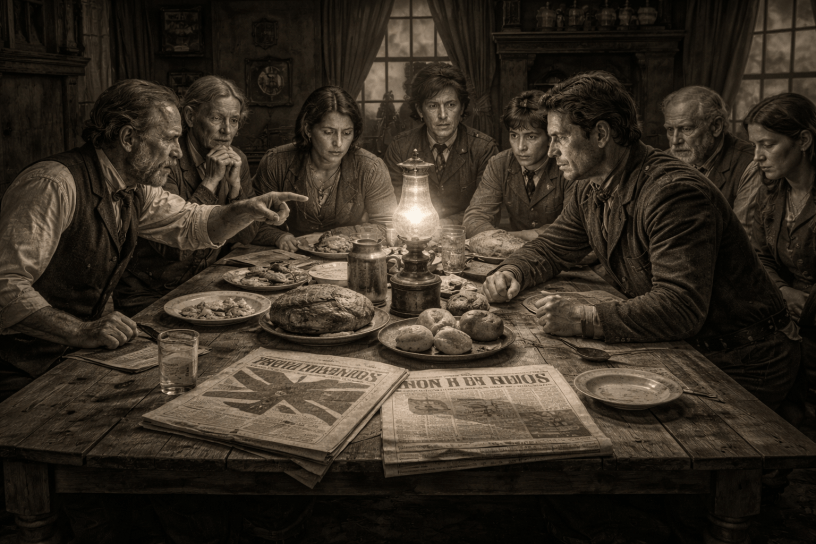

Long before uniforms were donned or shots were fired, the American Civil War entered homes through conversation. It arrived quietly, seated at the dinner table, embedded in prayers, jokes, and arguments that could no longer be smoothed over. Families did not need armies to feel the war approaching. They only needed to talk.

In the years leading up to open conflict, political allegiance ceased to be abstract. Questions that once belonged to newspapers or distant legislatures became personal. Slavery. Union. States’ rights. Loyalty. These were no longer positions held at arm’s length; they were statements about who someone was, what they believed, and whether they could still be trusted.

Politics Becomes Personal

For many households, disagreement had once been manageable. American political life was noisy but familiar, and families had long learned to coexist with differing views. What changed in the late 1850s was not disagreement itself, but its moral intensity. Positions hardened. Compromise began to look like betrayal.

Diaries and letters from the period reveal an increasing reluctance to speak openly at home. Writers mention “avoiding the subject” with parents, siblings, or spouses. Silence became a form of peacekeeping. Where silence failed, tension followed.

The dinner table, once a place of routine and reassurance, became a test of allegiance.

Families Divided

No line divided households cleanly. In border states and mixed communities, families found themselves internally split. Brothers argued. Cousins stopped visiting. In some cases, marriages strained under incompatible loyalties. A vote cast, a newspaper subscribed to, or a sermon praised could spark days of quiet hostility.

These divisions were not theatrical. They were wearying. People still had to eat together, work together, and share space. The war’s earliest toll was not physical but emotional—measured in unease, restraint, and the slow erosion of intimacy.

Churches, Communities, and Moral Sorting

Faith communities mirrored the household fracture. Churches that had anchored civic life became sites of contention. Clergy faced pressure to declare positions from the pulpit. Congregants listened not just for scripture, but for political cues.

In many towns, church splits preceded military ones. Congregations divided along sectional lines, forming new institutions that reflected competing moral frameworks. The result was a thinning of shared civic space. People still gathered, but no longer together.

This sorting effect extended outward. Social circles tightened. Friendships cooled. Invitations stopped coming. Choosing sides was not always a single decision, but a series of small ones that accumulated into separation.

The Cost of Moral Certainty

As convictions hardened, tolerance shrank. What had once been “a difference of opinion” became evidence of flawed character. Trust, once assumed, now required proof.

This shift mattered because it reshaped how communities responded when war finally came. Neighbors who no longer trusted one another were quicker to suspect disloyalty. Families already fractured by belief were less able to withstand the additional strain of absence, loss, and scarcity.

The war did not invent these divisions. It exploited them.

Living With Unresolved Conflict

For many Americans, the most exhausting aspect of this period was not choosing a side, but living with those who chose differently. There was no clean escape. One could not simply leave one’s family, church, or town.

So people adapted. Some compartmentalized. Others withdrew. A few leaned into argument, accepting conflict as unavoidable. None of these strategies restored harmony; they merely delayed reckoning.

By the time fighting began in earnest, the war had already redrawn the emotional map of the country.

Looking Back

When historians later described the nation as “divided,” they often meant states and armies. But the division began much closer to home. It began in rooms where people still loved one another but no longer understood how to speak without harm.

This is the second quiet truth of civic breakdown: before societies split publicly, they split privately. Before banners are raised, voices lower. Before shots are fired, meals grow tense.

The American Civil War did not start at Fort Sumter for most people. It started when the dinner table stopped being a safe place.

For more social commentary, please see Occupy 2.5 at https://Occupy25.com

McPherson, J. M. (1988). Battle cry of freedom: The Civil War era. Oxford University Press.

McCurry, S. (2010). Confederate reckoning: Power and politics in the Civil War South. Harvard University Press.

Faust, D. G. (1996). Mothers of invention: Women of the slaveholding South in the American Civil War. University of North Carolina Press.

Blight, D. W. (2001). Race and reunion: The Civil War in American memory. Harvard University Press.

Library of Congress. (n.d.). Civil War diaries and letters. Manuscript Division. https://www.loc.gov/collections/civil-war

Library of Congress. (n.d.). Chronicling America: Historic American newspapers. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov

Discover more from WPS News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.