By Cliff Potts, CSO, and Editor-in-Chief of WPS News

Before this series begins—before the battles, before the dates, before the familiar names—we need to stop and ask a question that still echoes today:

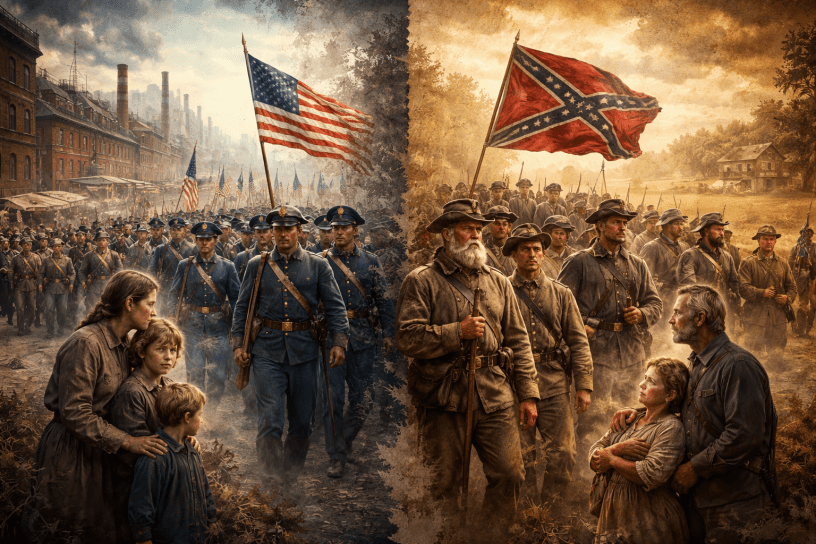

Why do different parts of the United States relate so differently to military service?

Look at enlistment patterns now and a strange paradox appears. The North, which won the Civil War and emerged with economic and political power, tends to show less cultural enthusiasm for military life. The South, which lost, still produces a disproportionate share of volunteers and maintains a strong military identity.

This essay is not an argument that the Civil War “caused” that difference in a simple way. History almost never works that cleanly. What the war did instead was leave behind different memories, and those memories shaped culture, opportunity, and identity in ways that still matter.

This article is the prequel to an 18-month WPS News series examining how the Civil War affected civilian life between 1860 and 1865. To understand what happened during the war, we first need to understand what it left behind.

The War Left Two Very Different Emotional Legacies

In the North, the Civil War came to be remembered as necessary—but deeply traumatic.

The Union draft was unpopular and disruptive. Conscription, substitution fees that allowed the wealthy to avoid service, and violent draft riots—especially in major cities—burned the idea of state-forced service into public memory. For many Northern civilians, the war became associated not with glory, but with coercion, class inequality, and intrusion into private life.

After the war, Northern society leaned hard into civilian paths: industry, commerce, education, and civic institutions. Military service wasn’t rejected outright, but it wasn’t romanticized either. Success, status, and mobility increasingly came from civilian systems, not uniforms.

In the South, the emotional aftermath was very different.

Defeat stripped away political power, economic security, and public dignity. In that vacuum, military service was reframed—not as failure, but as honor. Sacrifice, endurance, and loyalty became central to identity. The mythology that followed did more than rewrite history; it preserved military virtue as one of the few uncontested sources of pride left standing.

That distinction matters.

The Draft Changed How the North Thought About War

The Union draft did lasting cultural damage—and not without reason.

It exposed how unevenly the burdens of war were shared. It taught civilians that wars could be imposed from above, regardless of consent. And it normalized skepticism toward military authority, wars of choice, and compulsory service.

That skepticism didn’t turn the North into pacifists. But it did plant a habit of questioning power—especially when that power demanded lives. Over time, those attitudes became cultural inheritance. The details faded. The instincts remained.

Southern Enlistment Is About Structure, Not Bloodlust

Modern enlistment patterns in the South are often misread as enthusiasm for war. That’s a mistake.

They correlate far more strongly with structural realities: fewer civilian opportunities, rural demographics, weaker civilian institutions, and stronger traditions of hierarchy and inherited identity. Military service offers stability, recognition, and a clear path in places where civilian systems often fail to reward effort.

The Civil War didn’t create those conditions—but it locked in a powerful cultural script:

Service proves worth when civilian systems don’t.

In much of the North, a different script took hold:

Success is civilian. The military is a detour.

Neither script is universal. But both are durable.

The Paradox Is Real—and Telling

Here is the irony that sits at the center of this series:

The Union won the war—and grew more suspicious of militarism.

The Confederacy lost—and preserved military identity as cultural glue.

This pattern is not unique to the United States. In many post-conflict societies, victory leads to normalization and civilian focus, while defeat freezes identity around sacrifice and honor. The Civil War followed that same human logic.

This Is About Memory, Not Ideology

Most people who enlist today are not thinking about the 1860s.

But they are inheriting family stories, regional narratives, ideas about dignity, mobility, duty, and respect. They are absorbing assumptions about which paths are honorable and which are merely practical.

Those assumptions have roots. The Civil War is one of the deepest.

Why This Series Starts Here

This WPS News series will examine civilian life during the Civil War—families, labor, displacement, hunger, fear, survival, and adaptation. It will focus less on generals and more on households. Less on strategy and more on consequences.

But before we march into that history, we needed to clear the ground.

Wars don’t end when the shooting stops. They echo forward through memory, culture, and institutions. They shape how societies reward effort, define honor, and decide who serves—and why.

This series begins with the war.

But it is really about what came after.

For more social commentary, please see Occupy 2.5 at https://Occupy25.com

APA Citations

Blight, D. W. (2001). Race and reunion: The Civil War in American memory. Harvard University Press.

McPherson, J. M. (1988). Battle cry of freedom: The Civil War era. Oxford University Press.

Neely, M. E. (1991). The fate of liberty: Abraham Lincoln and civil liberties. Oxford University Press.

Rothman, A. (2005). Slave country: American expansion and the origins of the Deep South. Harvard University Press.

Skocpol, T. (1992). Protecting soldiers and mothers: The political origins of social policy in the United States. Harvard University Press.

Discover more from WPS News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.