By Cliff Potts, CSO, and Editor-in-Chief of WPS News

Baybay City, Leyte, Philippines — February 4, 2026

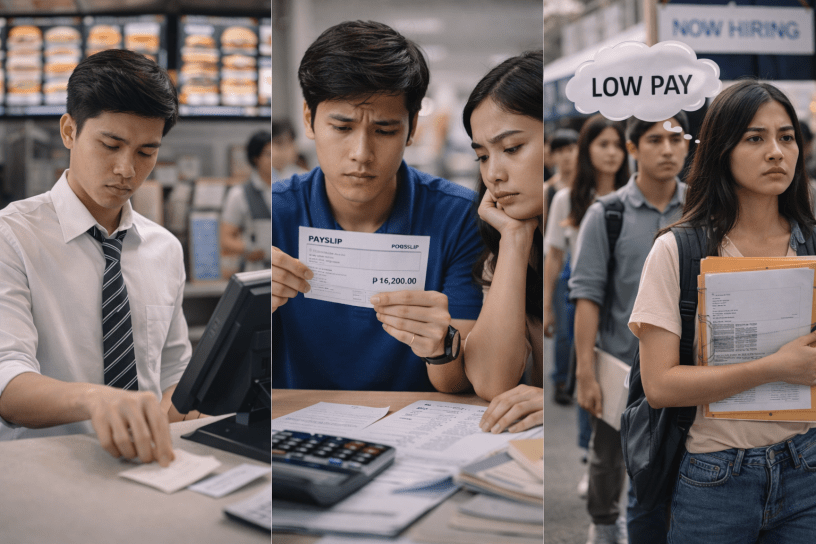

Low entry-level wages are not merely a social concern in the Philippines; they represent a structural economic constraint that limits productivity, weakens domestic demand, and distorts labor-market behavior. For many young Filipinos, employment no longer guarantees basic economic security, undermining the very purpose of work as a stabilizing force.

This analysis examines low starting wages through a chief strategy officer lens, focusing on market incentives, firm behavior, and policy options that are economically credible and operationally realistic.

The Entry-Wage Problem Defined

Entry-level wages in the Philippines have failed to keep pace with the cost of living, particularly in urban and growth corridors. While headline employment figures remain strong, real purchasing power for new workers has stagnated or declined.

From a systems perspective, this creates a critical failure: employment exists, but income adequacy does not.

Key indicators of the problem include:

- Starting wages below living-cost thresholds

- Minimal wage progression during the first years of employment

- Rising reliance on secondary income sources

- Persistent underemployment among educated workers

Low entry wages are not temporary frictions; they have become normalized.

Why Firms Suppress Starting Wages

Firms do not set low wages arbitrarily. Several structural factors drive this behavior:

- High labor supply relative to quality jobs

- Weak bargaining power among young workers

- Competitive pressure in low-margin sectors

- Limited linkage between productivity gains and pay

However, suppressing entry wages produces unintended consequences. Workers cycle rapidly between jobs, firms absorb repeated training costs, and productivity gains fail to compound. What appears cost-efficient becomes operationally inefficient over time.

The Macroeconomic Drag

Low wages suppress consumption. Young workers delay housing, reduce discretionary spending, and avoid long-term financial commitments. This weakens downstream industries—real estate, retail, services—that depend on stable consumer demand.

It also affects human capital development. When early-career work does not support basic living needs, workers rationally disengage from skill-building and long-term firm loyalty.

From a national perspective, low wages reduce the return on investment in education.

Why Minimum Wage Adjustments Are Insufficient

Minimum wage increases are often proposed as the primary solution. While necessary in some contexts, they are not sufficient on their own.

Uniform wage mandates:

- Do not account for productivity differences

- Can discourage formal hiring in small firms

- Often fail to reach contractual or informal workers

Without complementary measures, wage floors address symptoms rather than causes.

Evidence-Based Strategic Options

Effective solutions must increase wage capacity, not just wage mandates.

Productivity-Linked Wage Progression

Encourage structured wage ladders tied to verified skill acquisition and performance benchmarks. This aligns pay increases with measurable output rather than tenure alone.

Targeted Wage Subsidies

Use time-bound wage subsidies for early-career workers in priority sectors. These reduce employer risk while allowing workers to earn above subsistence wages during skill ramp-up periods.

SME Cost Relief

Offset payroll burdens for small and medium enterprises through social insurance pooling or tax credits, conditional on wage progression commitments.

Sectoral Wage Setting

Move beyond uniform wage floors toward sector-based standards that reflect productivity and cost structures. Countries using sectoral bargaining achieve higher wage adequacy with fewer distortions.

Transparency in Pay Structures

Require clearer disclosure of wage progression pathways. Workers who can see future income trajectories are more likely to invest effort and remain with firms.

Strategic Payoff

Raising effective entry wages produces measurable benefits:

- Higher retention and lower turnover

- Increased domestic consumption

- Faster skills accumulation

- Improved firm productivity

- Reduced pressure to seek overseas work

These outcomes are repeatedly observed in middle-income economies that successfully upgraded their labor markets.

Conclusion

Low entry-level wages persist not because they are optimal, but because the current system externalizes the cost of workforce development onto workers themselves. A strategic response does not force firms to absorb unsustainable costs; it restructures incentives so that early-career employment becomes economically viable for both sides.

Until employment reliably provides economic security, Filipino workers will continue to treat jobs as temporary, loyalty as optional, and migration as rational.

References

Philippine Statistics Authority. (2024). Wage structure and earnings survey. Quezon City, Philippines.

International Labour Organization. (2023). Global wage report: Real wages and inequality. Geneva, Switzerland.

Asian Development Bank. (2023). Labor productivity and wage dynamics in Southeast Asia. Manila: ADB.

Discover more from WPS News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.