By Cliff Potts, CSO, and Editor-in-Chief of WPS News

Baybay City, Leyte, Philippines — January 19, 2026

What Is Known

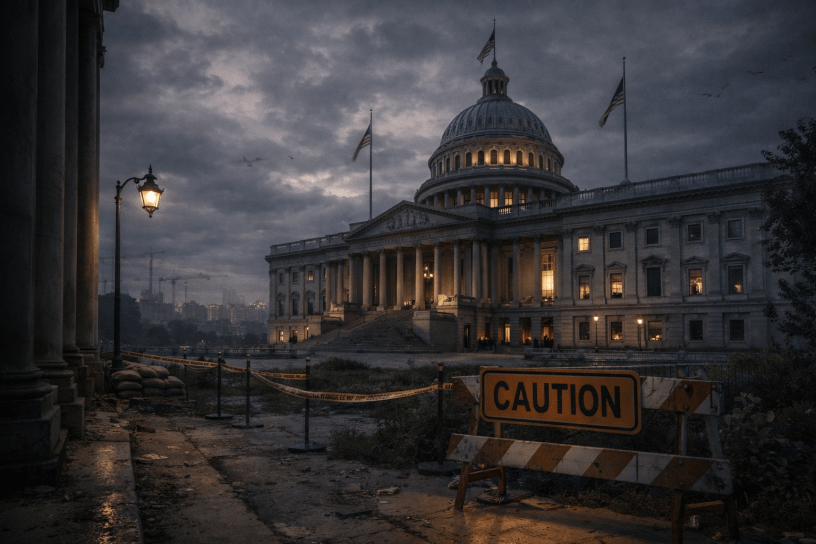

Across the Western world, core institutions remain intact. Governments continue to operate. Courts issue rulings. Elections are held. Financial markets function within expected parameters. International organizations meet regularly and issue communiqués that affirm continuity.

On the surface, this suggests resilience.

At the same time, structural indicators tell a more complicated story. Public confidence in political institutions has declined across most advanced democracies. Legislative bodies struggle to pass durable reforms. Executive authority increasingly relies on emergency powers, executive orders, or regulatory workarounds rather than broad consensus.

Economically, many Western states are managing persistent debt loads while assuming long-term growth that remains uncertain. Social systems—healthcare, housing, education—are under visible strain, even in high-income countries. These pressures are widely documented, but often treated as isolated policy challenges rather than interconnected risks.

Stability, in this context, is defined less by public confidence than by continued operation.

What Stability Now Means

In earlier periods, stability implied adaptability. Institutions were expected to respond to changing conditions, correct failures, and rebuild legitimacy when trust eroded.

Today, stability is increasingly defined as endurance.

Western systems are optimized to avoid disruption rather than to pursue reform. Political incentives reward short-term crisis management over structural change. Electoral cycles encourage postponement rather than resolution. As a result, problems accumulate even as the appearance of order is maintained.

This distinction matters. A system can remain stable while becoming progressively less responsive. It can function normally while narrowing the range of outcomes it can safely tolerate.

From outside the Western political environment, this pattern is increasingly visible.

Analysis: Inertia as a Governing Strategy

The illusion of stability is sustained by inertia.

Rules continue to be enforced because they already exist. Budgets are passed because default mechanisms compel them forward. Alliances persist because dissolving them would require political courage that few leaders are willing to risk.

This creates a form of governance by momentum. Decisions are made to preserve existing arrangements, even when those arrangements no longer address underlying conditions. Reform becomes incremental by necessity, not by design.

From a strategic perspective, inertia is not neutral. It favors established power centers, entrenched interests, and legacy systems. It also discourages honest reassessment, because acknowledging structural weakness introduces uncertainty that political actors are incentivized to avoid.

The result is a widening gap between institutional performance and public expectation.

External Perceptions Matter

For much of the Global South, Western stability now appears procedural rather than substantive.

Countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America increasingly plan on the assumption that Western leadership will be inconsistent, internally constrained, and reactive. This does not imply hostility. It reflects risk management.

Trade relationships are diversified. Security partnerships are hedged. Diplomatic alignment is treated as situational rather than permanent.

From this perspective, the illusion of Western stability is not persuasive. What matters is predictability, not rhetoric.

Where the Illusion Breaks Down

Illusions persist until they encounter stress they cannot absorb.

In the Western context, those stress points are accumulating: contested elections, prolonged wars without clear objectives, economic shocks layered on existing inequality, and information environments that undermine shared reality.

None of these guarantee collapse. They do, however, narrow the margin for error.

A system that prioritizes the appearance of stability over adaptation becomes increasingly brittle. When correction is delayed too long, adjustment tends to occur abruptly.

What Comes Next

The critical question is not whether Western institutions can continue to operate. They can, and likely will, for some time.

The question is whether endurance is being mistaken for health.

This series will continue to examine where that distinction matters most—particularly as other regions adjust their strategies based on what they see, not what they are told.

For more social commentary, please see Occupy 2.5 at https://Occupy25.com

This essay is archived as part of the ongoing WPS News Monthly Brief Series available through Amazon.

References

Fukuyama, F. (2018). Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2018). How Democracies Die. Crown Publishing Group.

OECD. (2024). Trust in Government: Trends and Drivers. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Discover more from WPS News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.