By Cliff Potts, CSO, and Editor-in-Chief of WPS News

Baybay City, Leyte, Philippines — February 19, 2026

For readers outside the United States, it is easy to assume that impeachment removes a president. In the American system, that assumption is wrong. Impeachment begins in the House of Representatives, but removal lives or dies in the Senate.

The Senate is not designed to be responsive to public pressure in the short term. It is designed to be resistant to it.

Unlike the House, where members serve two-year terms, U.S. senators serve six-year terms. Only one-third of the Senate is elected in any election cycle. This staggered structure slows political swings and insulates the chamber from sudden changes in public opinion.

That design choice has direct consequences during impeachment.

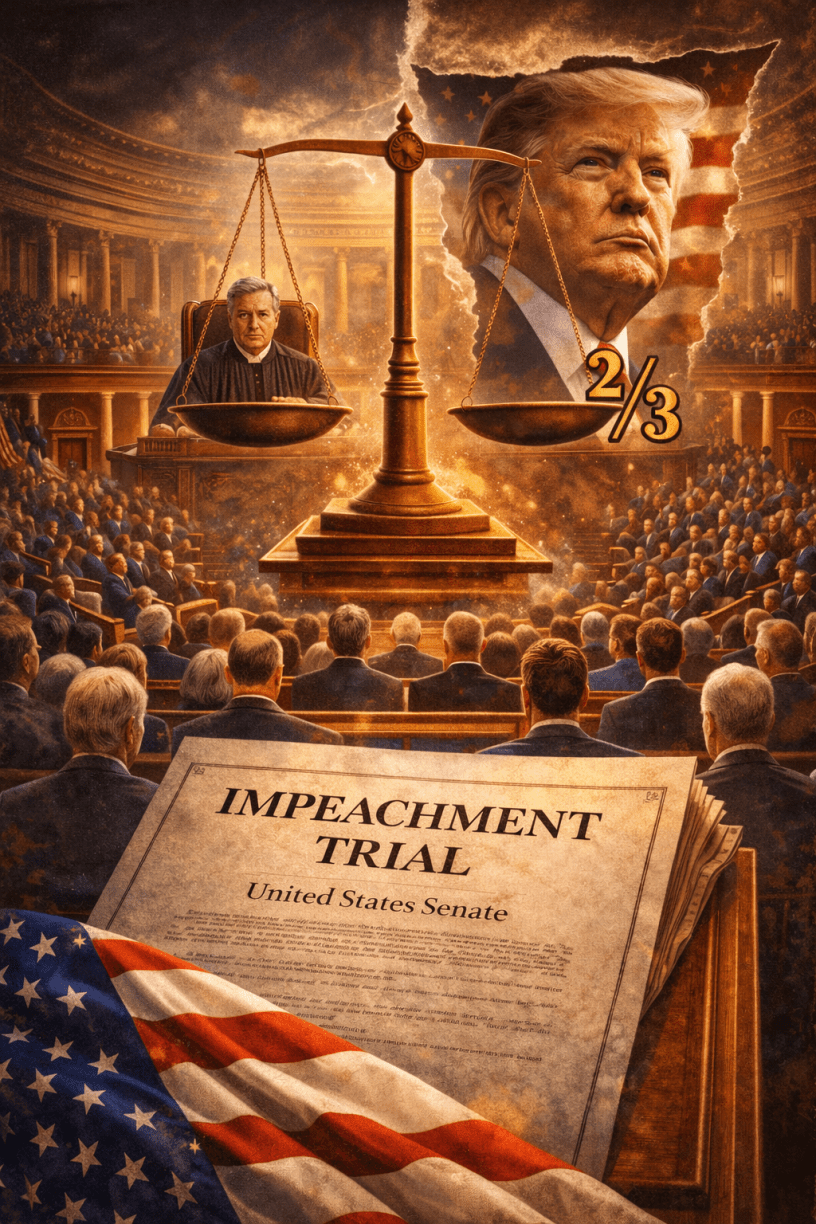

When articles of impeachment are sent from the House, the Senate conducts a trial. Senators act as jurors. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court presides. Conviction — and therefore removal — requires a two-thirds vote of the Senate.

This is an extremely high threshold.

It means that removal is impossible without substantial support from the president’s own party. Party loyalty, institutional caution, and fear of political retaliation all work against reaching that threshold. The system is intentionally biased toward continuity.

As a result, no president in U.S. history has ever been removed from office following impeachment.

This does not mean impeachment is meaningless. It means its consequences are different than many observers expect. Senate trials establish historical record, clarify misconduct, and shape political legacy. They rarely end presidencies.

The composition of the Senate matters more than headlines. Even if opposition parties gain seats in midterm elections, they must still reach or approach a two-thirds majority to remove a president. That is a level of consensus rarely seen in modern American politics.

Timing further limits expectations.

If Senate control shifts in the 2026 elections, that shift does not take effect until January 3, 2027. Even then, only one-third of senators will be new. The remaining two-thirds were elected earlier and are not immediately accountable to the current political moment.

For governments in the European Union and for countries in Asia, including the Philippines, this explains why impeachment is watched cautiously rather than celebrated. Senate trials signal stress inside the U.S. system, but they do not guarantee resolution.

The Senate’s role is to prevent rapid removal unless national consensus is overwhelming. In periods of polarization, that consensus is rare by design.

This is why impeachment often feels like an ending to observers — and like a stalemate to those who understand the system.

The Senate is the final gate. It is also the hardest one to open.

For more social commentary, please see Occupy 2.5 at https://Occupy25.com

References

U.S. Constitution, Article I, Sections 2–3.

Congressional Research Service. (2024). Impeachment and removal: Senate trial procedures.

United States Senate. (n.d.). Impeachment: Powers and procedures.

Discover more from WPS News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.